Embodied Standpoint Literacy: A Critical and Relational Practice of Shared Spaces and Struggles

by Temitope Ojedele-Adejumo

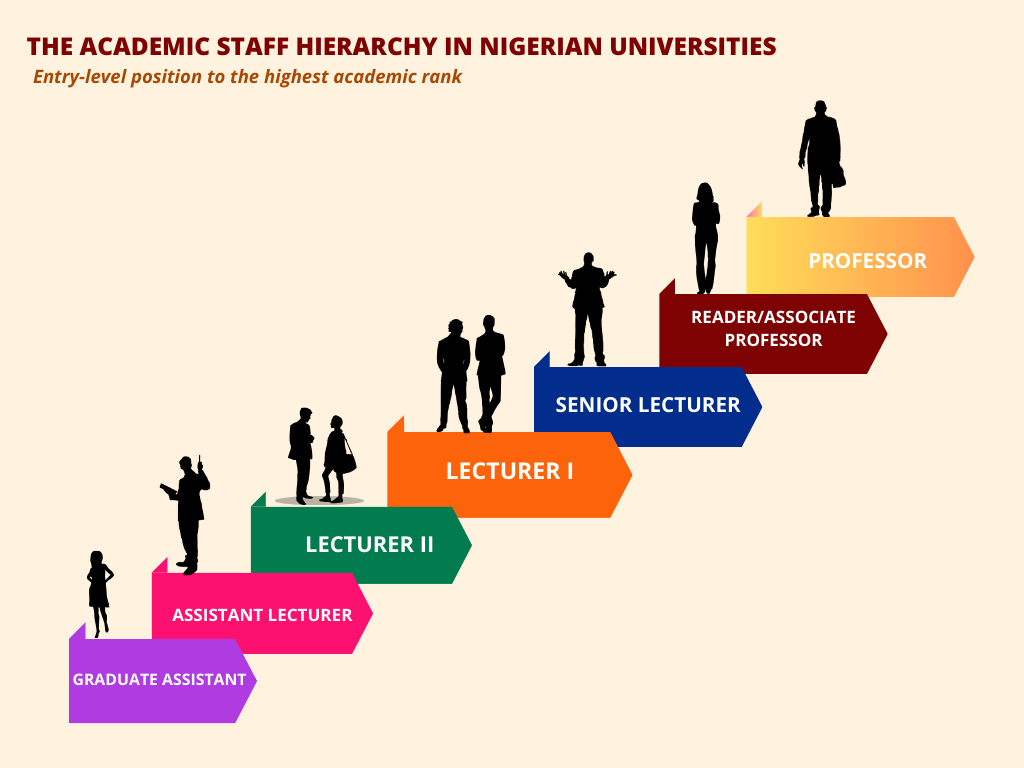

I had just been retained as a Graduate Assistant (GA) at the University of Lagos. My responsibilities included assisting professors with teaching, grading scripts, performing some administrative duties, coordinating examinations for visually impaired students, and invigilating exams. In short, a GA occupies the lowest rank on the academic ladder and is the first person that comes to mind for professors whenever they need assistance with anything. Students are well aware of the GA’s near slave-like status. And although the Nigerian higher education system – like other educational levels – places immense value on respecting professors or anyone in a teaching or mentoring role, that respect rarely extends to GAs, especially from senior students. The best-case scenario is that some students might consider you a friend or someone they can go to for help, especially if you’re assisting a professor who’s rarely around to teach their course.

So on one of the exam days, I was invigilating on behalf of a very senior faculty member. When it was time to collect the answer booklets, I approached a female student who had barely written anything. I expected that, in my role as a GA representing a senior professor, I’d receive some level of respect – if not for myself, then for the ethos I was momentarily borrowing as a representative of that professor. But the student didn’t budge. She simply placed her pen in her mouth and stared at me coldly.

“If you don’t give me your booklet now, you’ll have to grade it yourself,” I said. Still, she didn’t move.

I walked away, collected the rest of the booklets, and was getting ready to leave when the professor arrived. Sensing something was off, he asked what had happened. After I explained, he turned to the student and bellowed at her to apologize. She did. Then, with a tone of even greater authority, he said, “I know you disrespected her because she is a GA. In fact, go on your knees and apologize to her.” Going on one’s knees to apologize is a cultural expression of deep respect and a way to acknowledge the authority or seniority of the person being apologized to in Nigerian society.

At that moment, I felt deeply uncomfortable. While the student had indeed been disrespectful, and likely would have acted differently if it had been the professor collecting the booklets, I didn’t believe that going on her knees to apologize was appropriate. I didn’t want anyone on their knees for me. I told the professor it was fine, that she didn’t need to do that. But he insisted, saying he wouldn’t collect her booklet unless she complied. To my utter embarrassment, the student obeyed. If the professor thought making her kneel before me would make me feel respected, the gesture failed. Instead, I felt like his power had been abused and I had become complicit.

After completing the exam duties and organizing the booklets, I headed back to my office. On the staircase in the department building, I ran into the student again. I stopped her to talk about what had happened, and she immediately burst into tears. I took her to my office and gave her time to collect herself.

Eventually, she opened up. She told me she had not meant to be disrespectful to me but was angry at herself. She explained how hard she had studied for the exam, how much effort she had put in, only to go blank in the exam hall and be unable to answer any of the questions. We spoke at length. I shared advice about more effective study strategies, reassured her that she could retake the course, and, most importantly, apologized for not recognizing her distress earlier and for the way the professor had handled the situation. Then she left.

A couple of years later, I found myself teaching a First-Year Writing class in the U.S. – a different continent, with different expectations, different beliefs, and different students. One of the core conversations in the first phase of this required university writing course is the subject of literacy.

In my class, I intentionally made room for alternative approaches to literacy, especially to accommodate my international students and to reflect the reality that traditional definitions of literacy no longer capture the wide range of ways we engage with the world today. I introduced the concept of alternative literacy, and this became a central lens through which students approached their major projects.

However, I had one student who, despite how intentionally I had designed the course to support different approaches, still couldn’t connect with any particular form of literacy – not even one that helped them make sense of their academic world. I couldn’t quite process this. I was growing increasingly frustrated by what I perceived as the student’s nonchalance, even after we’d had a one-on-one conference.

In the midst of this confusion, I attended a conference where a presenter used the term anti-literacy to describe certain student experiences. That term stuck with me. It powerfully captured everything I had been reflecting on with regard to this student. During our second individual conference, I asked the student about their general feelings toward the class and its expectations. They told me they genuinely enjoyed the class, but they still couldn’t articulate what literacy meant to them, not even in a non-traditional or alternative form. Then I asked what they thought about the idea of anti-literacy.

It was magical. They lit up and said the term perfectly described how they felt. They began talking about how their learning experiences in middle and high school had ruined education for them. If they had their way, they wouldn’t be in school at all. And more painfully, they couldn’t even imagine an alternative literacy that wasn’t somehow tied to school; an institution that had consistently failed them. They went on to say that they were speaking to a counselor because they knew they needed to maintain a good grade to remain eligible as a student-athlete. So, I encouraged them to approach their assignment through the lens of anti-literacy. That shift made all the difference. They were able to complete the rest of the course projects by framing their narratives through this perspective.

As I continue in my budding journey as an instructor, these two experiences have remained significant and continue to shape how I approach and respond to students.

Progressively, as I embark on my PhD dissertation, my research has evolved into the development of a concept I call Embodied Standpoint Literacy (EmSL), which I will use to explore the literate activities of Anglophone African graduate students in the U.S. EmSL represents a confluence of Canagarajah’s (2019) literacy autobiography (LA), Prior and Shipka’s (2003) concept of chronotopic lamination, and LaFrance’s (2019) articulation of standpoint, as theorized by Dorothy Smith. In other words, I theorize EmSL as a strategic literate practice that negotiates the interplay of personal, cultural, transnational, and institutional layers to achieve a rhetorical effect.

While it’s natural to focus primarily on students, EmSL also serves as a valuable tool for understanding the instructor’s perspective. The Literacy Narrative, for example, is a self-expressive genre adopted by the University Writing Program to create space for students to integrate their lived experiences with scholarly discourse. However, even that provision wasn’t enough to capture the experience of my “anti-literacy” student. As for me, the instructor, my sustained patience in not judging this student’s attitude toward their work, especially given their strong attendance, was rooted in my earlier encounter with the female student during an exam in Nigeria. That experience taught me the importance of holding space for students whose struggles with literacy may not always be visible or easily articulated.

In fact, I’ve come to understand that my empathy for the female student in Nigeria, and the embarrassment I felt during that encounter, stemmed from a shared embodiment. The professor was male, while the student and I were both females. He belonged to a much older generation, whereas I shared a closer generational orientation with the student. I did not agree with the approach the professor took to address the situation, and that conflict deepened my sense of discomfort and connection with the student. Moreover, my own status as a GA tasked with doing so much work for professors as a result of institutional power relations also shaped how I interpreted the professor’s actions. His approach reflected a particular wielding of power that I had been subject to myself, and at that moment, I saw how those same dynamics were being imposed on the student. This layered identification with the student’s gender, generation, and subordinate position within the academic hierarchy intensified both my empathy and my unease.

Also, as an instructor in a predominantly white institution, my decision to design my curriculum to make room for exploring alternative forms of literacy, particularly to better support my non-Western students, stems from my own experience as an international student. I’ve been part of classes where issues were approached solely from a Western perspective, even when I knew those same issues existed in my own culture, albeit in different forms. That sense of exclusion made it clear to me how important it is to create space for multiple ways of knowing and being.

Hence, when we think of EmSL as a critical pedagogical tool that serves both the student and the instructor, we begin to understand that literacy is not a fixed or neutral skillset. The student, just like the instructor, brings an embodied standpoint shaped by culture, language, personal history, and institutional context. EmSL makes space for these intersections, allowing both parties to navigate literacy not just as a cognitive process, but as a lived, relational, and strategic practice.

Fundamentally, it is important to recognize that when individuals enter a shared space with their respective embodied standpoints, conflicts are bound to arise. However, understanding and acknowledging these differing perspectives can foster a more inclusive and empathetic environment.

For example, although I strive to support the welfare of my students, I once had a student who abused my goodwill, repeatedly lying for their own benefit, which took a toll on me emotionally and mentally. In that situation, institutional agents were quick to protect the student, casting me, the instructor, as the villain. This experience revealed a structural imbalance: while students in U.S. higher education are often treated as consumers whose rights and welfare must be safeguarded, the standpoint of the instructor is frequently overlooked.

Consequently, to protect myself from future embodied clashes, I now enter every class with clearly articulated policies that ask all participants to acknowledge and respect the shared space we are co-creating. These policies serve as a token of mutual accountability, ensuring that the diverse embodied standpoints in the classroom – including those of both students and instructor – are recognized and valued.

It is also important to note that whatever serves as the token of maintaining balance in our shared literacy spaces tends to work more effectively when it can adapt to ongoing change. For example, syllabi and class policies are typically communicated at the beginning of each semester. However, from experience, circumstances often shift for both instructor and students as the semester progresses. As a result, we might find ourselves having to revisit and revise those initial agreements to better reflect the evolving needs and realities of our classroom community.

In conclusion, while global and transnational education is the hallmark of academic engagement in our hypercultural world, EmSL serves as a tool to recognize and account for everyone’s differences, while also providing strategies to navigate and mitigate potential clashes.